Although the ILO advocates for the “Future of work we want” in the framework of its centenary celebration, discrimination and precarious work still remain realities within the Office. Discover here what ILO colleagues are suffering in their day to day life…

Ana has been working with dedication for the same employer for the last 15 years. As many of us do, she plans to buy a house. The bank, however, has turned her down: you can’t get a loan on a one-year contract. She wants to have a baby, but she’s not sure it’s sensible as her maternity leave would start after the end of her current contract. In fact, she’s constantly worried about not having a contract after the one she’s on, especially as she’s not entitled to unemployment benefit. But, like many other precarious workers, she dares not complain, because she doesn’t want to be seen as a trouble-maker.

You don’t know Ana? She works in the ILO!

Like many others, Ana works on the issues which are at the heart of the ILO, whilst her own rights to decent work are put on hold. Like many others, she promotes decent work and fundamental rights at work, supporting ILO constituents to implement them. This is the kind of job you do with passion and great pride.

You do know Ana: she’s one of the many ILO members of staff working on “DC” (which stands for “Development Cooperation”, formerly known as “TC” for “technical cooperation”, i.e non-regular budget) contracts. [1]

Ana is one of us. We feel privileged to be working at the heart of the ILO vision for social justice.

But, as staff members on DC contracts, we are always left aside.

NEARLY 45% of ILO staff are precarious workers

No one should be in this situation. At the ILO, over 4 in 10 workers (1381 total), i.e nearly half of the ILO workforce (professional and general service), are precarious workers (some of them with monthly contracts after more than 5, 10 or 15 years of service). In some branches, this percentage rises dramatically, to as much as 70% or more. In the field, over 55% of general service staff are employed on Development Cooperation contracts. All of these figures have increased in the last year (See: Composition and structure of the staff at 31 December 2018, GB.335/PFA/11).

We are not called “ILO staff”, we are called “ILO DC staff”. Two letters that make a world of a difference: a world of inequality and discrimination.

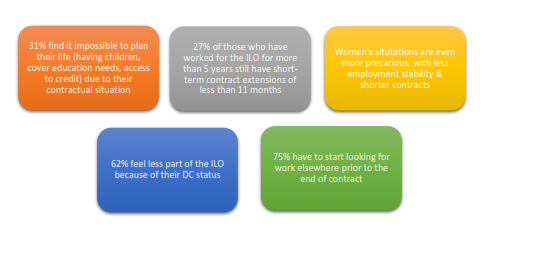

Survey results carried out by the Staff Union on DC staff show:

What would be the ILO’s impact in its Centenary year in the absence of the work done by DC staff? Many of the results reported to the international community in the Centenary year, and to the Governing body on key ILO outcomes, are mainly obtained through DC projects and DC staff. Would the ILO have been able to release the global estimates on child labour and forced labour? Would the ILO have been able to contribute to the work of the Joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)? What would the ILO’s Flagship Programme working to promote improved working conditions in garment industry supply chains look like in the absence of over 200 Better Work staff working across 8 countries?

A career based on short-term contracts

On paper, DC-funded staff are supposed to be doing DC work, short-term assignments, and specific project-related work. “Development cooperation appointments are not expected to lead to a career in the ILO“, as we are reminded at the beginning of all DC vacancy announcements.

The reality, however, is different: most of us have been here for many years; five, ten, fifteen, twenty, more, doing core ILO work, Regular Budget work! We raise funds. We represent the ILO in external meetings and events. We are the face of the ILO when dealing with constituents. We carry out research. We provide support and assistance to our constituents. We draft official reports of meetings. We contribute to the Programme and Budget reporting and monitoring. We carry out crucial administrative and financial tasks. So, on top of this being an issue of discrimination, it is also a structural issue as some core services are performed by staff which should hence be paid on RB instead of DC as they currently are.

Unequal and discriminatory practices

Although, most colleagues would find the situation unfair and unacceptable, they do not genuinely know what is like to be “DC”. In fact, many colleagues do not even realize we are under so-called, “DC contracts”. We say “so-called” because in the entire 124-page Staff Regulations – all 14 Chapters, plus five annexes – there is not a single solitary reference to “DC (nor TC) contracts”. In fact, a quick read of the Staff Regulations is instructive, as references to DC/TC are focused exclusively on “technical cooperation project staff” or “staff assigned to technical cooperation projects”. This further highlights the difference between how these arrangements were first conceived (to staff specific projects, of limited duration) and the situation into which it has morphed over time.

Let us introduce you to other colleagues (All cases in this article are real but names have been changed):

- Daniel’s contract is always renewed at the last moment, a few days or weeks before its end date.

- Mariam’s contracts have never exceeded a year, even when the ILO had received funding from the donor for several years. In fact, did you know the ILO can issue a DC contract for more than a year? Yes, it is possible but hardly ever done! Why?

- Emma has to sublet as she could not provide evidence of a stable employment needed to rent a flat.

- Sofia, Phil and Emily joined the ILO in the same year. Phil and Emily were awarded for 25 years of service by the DG, but Sofia was not, because she has been working on DC. Did her contribution to the ILO have less value?

- Moving is one of the most stressful things a family can face, and there is no difference in the administrative and logistical hurdles that Maria has to deal with in changing duty stations, compared with her RB colleagues. So why isn’t she granted the same leave to deal with the move?

- Shortly after Myra announced she was pregnant, her supervisor told her she would not be renewed.

- Jaya has been working for the ILO for more than 10 years but she has been without a contract for several weeks from time to time. As a consequence, when applying to regular positions over the years, she is still considered as an external candidate, despite her qualifications and years of ILO experience.

- Although Khaled is entitled to home leave, he has only taken it once in 8 years; continual short term contracts mean that he never has the 6+ months of contract duration upon return from home leave that is required for him to take it.

- After six years of service in the ILO, Oliver’s contract ended last month. He is applying for several positions but is now considered an external candidate, with no recognition of his long service to the organization.

- Nicola is never able to leave Switzerland during the Christmas break, as her contract is always renewed at the last moment, without enough time to have her legitimation card renewed beforehand.

- Santiago is often working during his holidays or leave, even during his sick leave. The workload is enormous, but he does not feel he can take breaks: if he doesn’t deliver the project outputs, he worries that he could lose his job.

- Mamadou is national project manager and, like many DC field colleagues, usually takes only a few days of annual leave as his workload doesn’t allow him to take more. However, this is no longer allowed as the Office limits what staff can accrue. But in his case, it was also a way for him to put money aside in view of the end of his precarious contract.

These are real cases of colleagues around you. This precariousness is the sword of Damocles hanging over our heads constantly, even after 10 years or more of serving the ILO. And when we are no longer needed, it is a simple “goodbye”: because we are DC, there is no further compensation. We are not fired, we are “just” not renewed. In the words of an HR colleague, uttered without much compassion “as DC staff, you should know the rules of the game“.

And this cannot even be mitigated with unemployment services, as the UN failed to negotiate with national authorities to allow staff to voluntarily contribute to unemployment schemes. So there is no safety net either.

Even with outstanding performance appraisals, strong skills and expertise, developed over many years, there is little career advancement, as we are not considered specialists (remember, because we should not expect a career at the ILO…).

Well, it is about time the rules changed and this discrimination in our midst ended.

Can the ILO lead the future of work without addressing these problems facing its own internal working conditions; giving rise to the ILO precariat?

Although some improvements have been made, such as the DC +5 status considered during the recruitment process there is still a long way to go: DC+5 means five years of continuous contract with the ILO without a break of more than a month – something DC staff often are unable to achieve.

We welcome the decision taken to re-establish the DC Committee within the Staff Union, and hope that it will begin its work soon, and seriously. We stand ready to help. We suggest you do the same. Contact the union at syndicat@ilo.org to get involved, to share your stories, and to help build “One ILO” where DC staff are no longer considered second-class workers.

As an organization fighting for decent work around the world, the ILO should stand for its staff, take risks for its staff. Ana, Daniel, Mariam, Khaled and all of us deserve equal rights and equal treatment.

We are calling for a roadmap to end this discrimination together with the management and the union and in full consultation with DC staff.

One ILO, one ILO staff.

A group of “DC” colleagues working at HQ

This message reflects the positions of a group of “DC” colleagues working at HQ, and the ILO Staff Union bears no responsibility for its content.

[1] All cases in this article are real but names have been changed